COVID-19 has interrupted our lives in ways that we never could have predicted. From closing schools to shuttering businesses, no one could have foreseen how much our lives would change in such a short period of time. As the economy begins to reopen, businesses and organizations are largely left to wade through the constantly evolving guidance on their own, trying their best to protect their employees, customers, and the general public from COVID-19 exposure. During this unprecedented time, we want to ensure that people with disabilities are not excluded from opportunities as we all venture back into our communities.

As there is currently no vaccine against COVID-19, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends the following behaviors to limit its potential spread:

Implementing this guidance can take many forms, however. While each of these behaviors is designed for individuals to follow themselves, most businesses have updated their company policies and procedures to incorporate them.

The following guide is designed to help you navigate how to maintain your property’s required accessible features and avoid the introduction of new COVID-related barriers that exclude people with disabilities, however unintended. While it was meant to be thorough, it is by no means exhaustive. It is important to remain flexible so that as we learn more information, we can incorporate any updated guidance and reflect upon its impact on people with disabilities.

As we celebrate and acknowledge the 30th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act this year, it is important that our commitment to the inclusion of people with disabilities does not waver, even as we are left to struggle with how to balance public health measures with individual and civil rights.

On July 26th, 1990, approximately 1,000 people with disabilities assembled on the White House lawn to watch President George H. W. Bush sign the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). As he signed the bill, President Bush said, “Let the shameful wall of exclusion finally come tumbling down.” It was a profound moment, and people with disabilities, not just on that lawn, but throughout the country, celebrated its passage by envisioning a future where they were embraced, included, and able to contribute.

The ADA serves as a guide for individuals, businesses, and government about how to address disability-related issues. Unnecessary separate or special treatment is a discriminatory practice, regardless of motivation. In fact, most disability discrimination is not rooted in ill will. Instead, it is based on unfamiliarity and outdated, ableist beliefs about disability—often masquerading as kindness. The ADA gives proactive instructions on how to include, hire, and serve people with disabilities without offense.

The ADA’s protections are expansive, but not unreasonable. It applies to the past, present, and future; from barriers that are familiar to ones not yet faced. The Internet and autonomous vehicles used in transit, for example, must comply with the ADA, despite the fact that neither the ADA’s drafters nor the overwhelming majority of Americans could imagine either at the time. While it is an all too common phrase to claim older buildings are “grandfathered in,” it is not accurate. Businesses, state and local governments must serve all people—and not just those without disabilities—and make modifications and accommodations to their programs, as needed. The ADA’s barrier removal requirements apply to accessibility concerns that can be removed in a “readily achievable” manner, i.e. without great difficulty or expense. That responsibility is ongoing, and if not removed between 1990 and today, they should be now.

The ADA diverges from previous civil rights laws by making it a discriminatory practice to not reasonably accommodate disability, that is, it changed nondiscrimination from a passive act to one that requires action, i.e. barrier removal, reasonable accommodation, etc. Merely refraining from treating people with disabilities badly is not all that is required.

As we face COVID-19 together, our focus must remain on protecting the health and safety of our communities, but it must not come at the cost of excluding people with disabilities or eliminating the gains made over the last 30 years due to the ADA.

Even though COVID-19 required businesses to react without warning or ability to prepare, it is important to not forget our ongoing obligation to provide equitable services for people with disabilities. Unfortunately, as soon as businesses began incorporating new policies and procedures to respond to COVID-19, our members as well as those from the greater disability community began noticing new barriers to accessibility that did not exist at those locations before.

In order to capture how COVID-19 policies have affected the disability community, either positively or negatively, United Spinal released a survey designed for people with disabilities or those who share their lives with people with disabilities (2).

When asked “What, if any, COVID-related barriers have you experienced while out in the community?” (3)

Not all changes have resulted in negative outcomes, however. Several respondents praised the increased availability of curbside pickup since it allows them to be more independent and less reliant on friends, family, or caregivers for assistance when completing errands. Also, as establishments removed furniture in order to promote social distancing indoors, many commented on how much easier it was to move throughout a space. Overwhelmingly, however, comments focused on the increased flexibility in service options, whether it is offering different pickup or delivery options, or how they conduct business (in person, over the phone, or by video), the biggest theme is that by having more options, the experience of people with disabilities has greatly improved.

Currently, the most widely accepted research suggests that maintaining a distance of at least 6 feet between people not within the same household helps limit COVID-19 transmission. While people should be responsible for keeping their own distance from others, businesses are making alterations to their spaces as well as implementing new practices and procedures to help nudge employees and visitors into more healthful behaviors. As you evaluate how best to keep everyone safe, it is important to consider how these changes might affect people with disabilities.

Since the ADA does not require every feature to be accessible when there are multiples of the same type, it is possible for a business to inadvertently remove a required accessible feature. Some features are more easily identifiable than others, however. For example, the accessible stall in a multi-user bathroom is something almost everyone can identify. In contrast, it might be more difficult to pick out an accessible sink in a row of sinks. Please refer to the Appendix: How to Identify Accessible Features to learn more about the most common accessible features of a business, such as accessible routes, accessible tables, door maneuvering clearances, and accessible sinks.

In order to limit exposure and prevent COVID-19 transmission, most jurisdictions have implemented restrictions on how many people can congregate inside at one time. While limited capacities are based on reduced percentages of existing occupancy standards, some businesses have expanded that mandate to include offering dedicated shopping hours to restricted populations (seniors and people with disabilities), limiting how many people from a single family can shop together, and providing pick-up only zones in the parking lot or at the curb to reduce the need to enter a store.

In addition to encouraging increased physical distance and limiting capacity within enclosed spaces, it is also a common practice for businesses to disinfect their properties, furnishings, and equipment more frequently with specific COVID-19 approved cleaning agents. However, not all cleaning agents are nonhazardous for people with disabilities.

Depending on where you are located, face masks may be required, encouraged, or simply left to the individual business to determine its own policy. The compulsory use of masks remains controversial, and while some

people may want to fraudulently take advantage of the ADA’s broad protections, there are certain disabilities that preclude the use of face masks. For example, the CDC recommends that “masks should not be worn by children under the age of two, or anyone who has trouble breathing, is unconscious, incapacitated, or otherwise unable to remove the mask without assistance (4). The Southeast ADA Center, in partnership with the Burton Blatt Institute at Syracuse University, expands that list to include people with:

Because it may be difficult to discern whether someone has a bona fide need to avoid using a mask, it is important to develop policies that acknowledge the existence of invisible or non-obvious disabilities and describe how employees should respond to a customer’s refusal to wear a mask (6).

Another disability-related concern regarding masks is how they might affect people who are d/Deaf and/or hard of hearing, who compromise roughly 15% of the American population aged 18 and older, or 37.5 million adults (8) . While having trouble hearing may not prevent someone from wearing a mask themselves, they will likely interfere with communication for those who rely on lip reading, have soft speech, or have difficulty hearing voices that are muffled by their usage.

The Americans with Disabilities Act requires businesses to communicate with people with disabilities in a way that is as effective for them as it is for others without disabilities. People who have difficulty seeing, hearing, speaking, comprehending, or reading may not be able to understand the rapidly evolving COVID-related chang es undertaken by a business if information is provided only one way. In order to communicate with as many people as possible, it is best for businesses to provide critical information in as many formats as possible.

The American Council of the Blind recommends printed documents should exhibit the following characteristics in order to be usable by the low vision community (9):

All COVID-19 related information should be posted on a business’ website and social media accounts. If you have concerns about your digital accessibility or would like confirmation that your content is accessible to people with disabilities, visit www.digital.gov, a program of the U.S. General Services Administration.

If possible, provide routine audible announcements regarding COVID-19 policies and be prepared to read signs to people who ask for assistance.

Businesses should also provide a contact number for anyone needing to discuss the COVID-related policies and practices in greater detail.

United Spinal Association

United Spinal Association is dedicated to enhancing the quality of life of all people living with spinal cord injuries and disorders (SCI/D), including veterans, and providing support and information to loved ones, care providers and professionals.

www.unitedspinal.org

Accessibility Services

Accessibility Services, a program of United Spinal, provides professional consulting services devoted exclusively to making our built environment accessible to people with disabilities.

www.accessibility-services.com

US Access Board

The U.S. Access Board is a federal agency that promotes equality for people with disabilities through leadership in accessible design and the development of accessibility guidelines and standards for the built environment, transportation, communication, medical diagnostic equipment, and information technology.

www.access-board.gov

US Department of Justice ADA Information

The ADA requires the Department of Justice to provide technical assistance to businesses, State and local governments, and individuals with rights or responsibilities under the law. The Department provides education and technical assistance through a variety of means to encourage voluntary compliance.

www.ada.gov

ADA National Network

The ADA National Network provides information, guidance and training on how to implement the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in order to support the mission of the ADA to “assure equality of opportunity, full participation, independent living, and economic self-sufficiency for individuals with disabilities.”

www.adata.org

For people who rely on accessibility, being able to identify which elements of a place are designed for people with disabilities becomes second nature. For business owners and their decision-makers, on the other hand, it might not be as obvious.

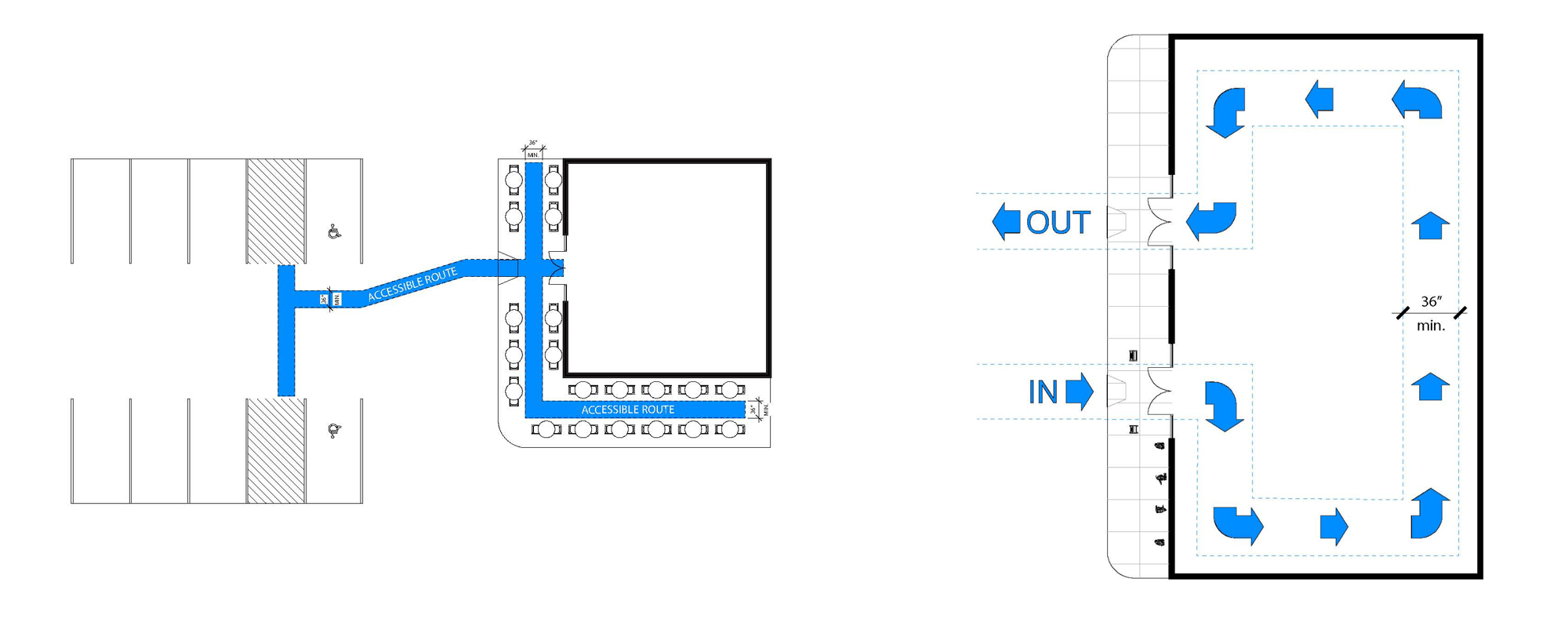

Accessible Route

An accessible route describes the continuous, unobstructed path connecting all interior and exterior accessible features of a location, such as arrival point (whether it is from public transportation, parking, or pedestrian access), entrances and exits, and if provided, public restrooms, sales and service counters, tables and seating, etc. An accessible route is typically 3 feet in width and should not have abrupt changes in level.

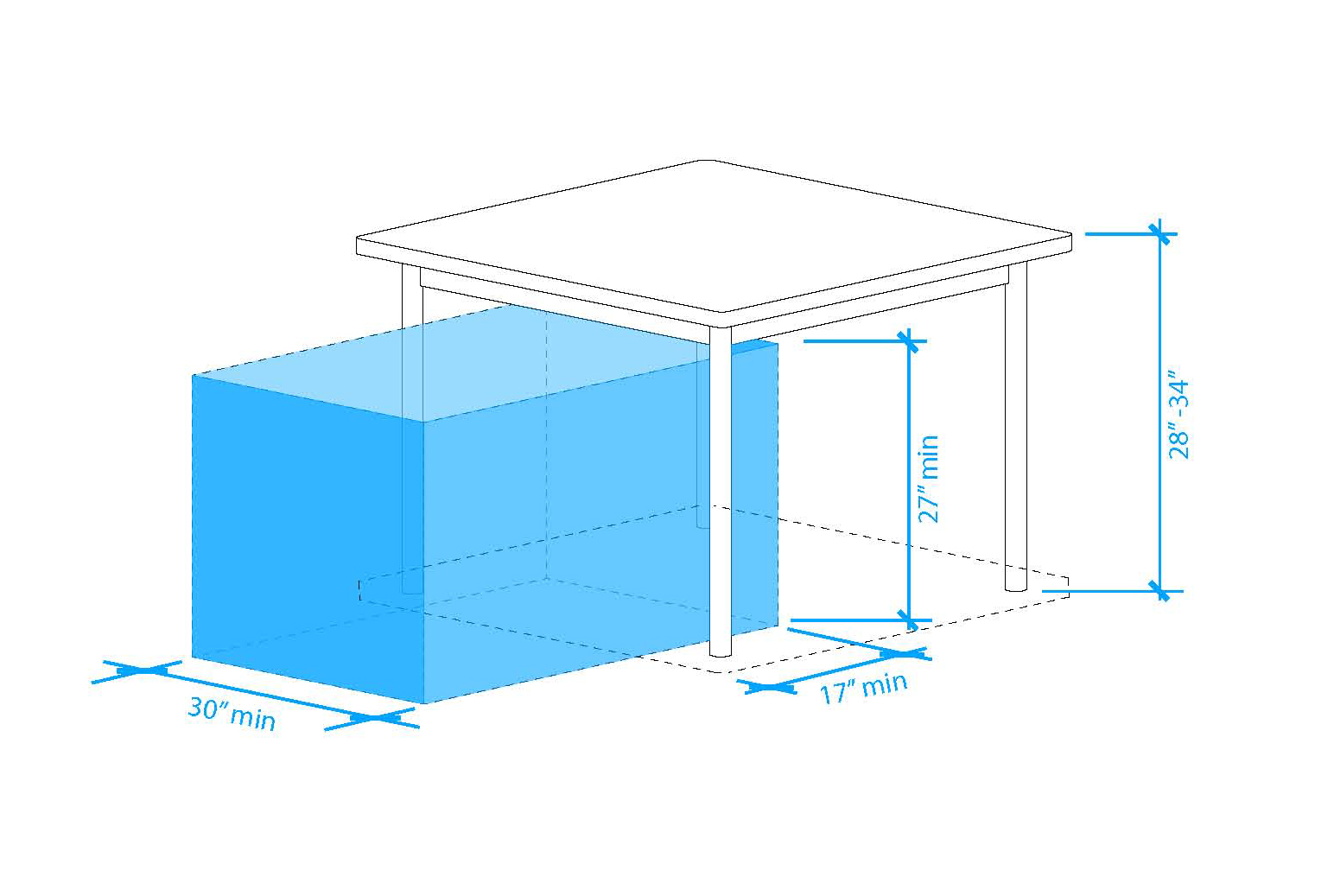

Accessible Tables

An accessible table has a surface height of 28 – 34 inches above the floor. It must also have at least 27 inches of knee clearance between the floor and the underside of the table with at least 17 inches of depth (lap coverage). Remember, accessible tables and seating must be dispersed throughout in order to reflect each type provided (bar seating, patio seating, dining room, etc.).

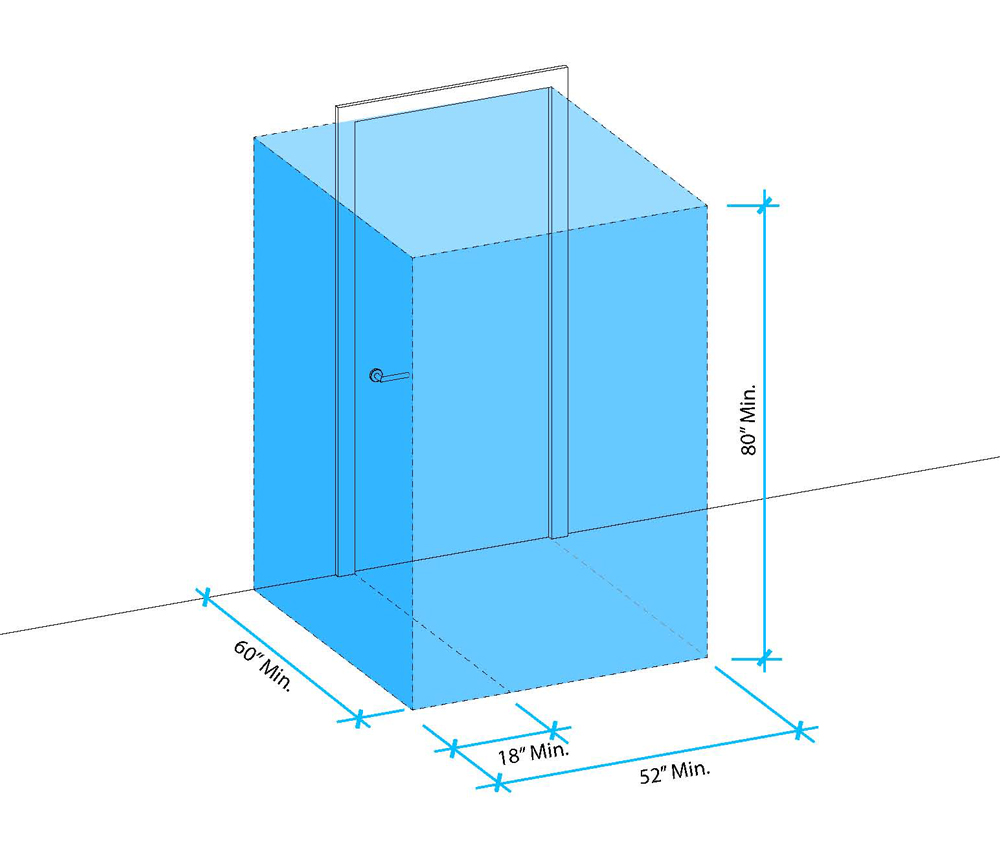

Door Maneuvering Clearance

Door maneuvering clearance describes the unobstructed space necessary for someone with a disability to open a door. There must 18 inches of clear floor space beyond the latch-side of the door and the approach must allow for 60 inches (5 feet) in depth.

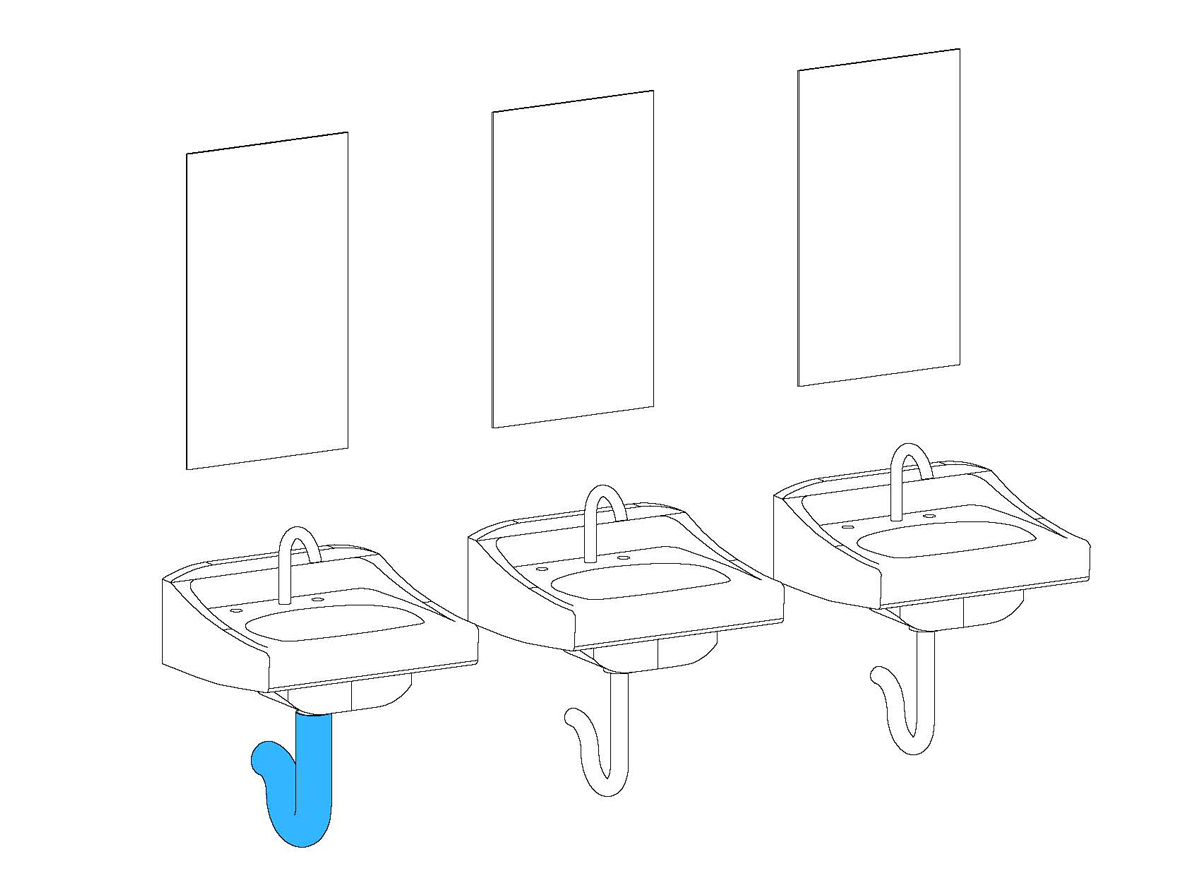

Accessible Sinks

An accessible sink has a maximum rim height of 34 inches above the floor and must provide adequate knee and toe clearance for a forward approach by someone using a wheelchair. Any exposed pipes must be protected from contact, which can be provided via wood panel or padded pipe insulation.

A best practices guide with regard to accommodation for employees and customers with disabilities or medical vulnerabilities.

(1) cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html

(2) forms.gle/B7SCHifKPkVBds3F8

(3) As of August 12, 2020

(4) epa.gov/saferchoice

(5) cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/cloth-face-cover-guidance.html

(6) adasoutheast.org/ada/publications/legal/ada-and-face-mask-policies.php

(7) justice.gov/opa/pr/department-justice-warns-inaccurate-flyers-and-postings-regarding-use-face-masks-and

(8) nidcd.nih.gov/health/statistics/quick-statistics-hearing

(9) acb.org/large-print-guidelines